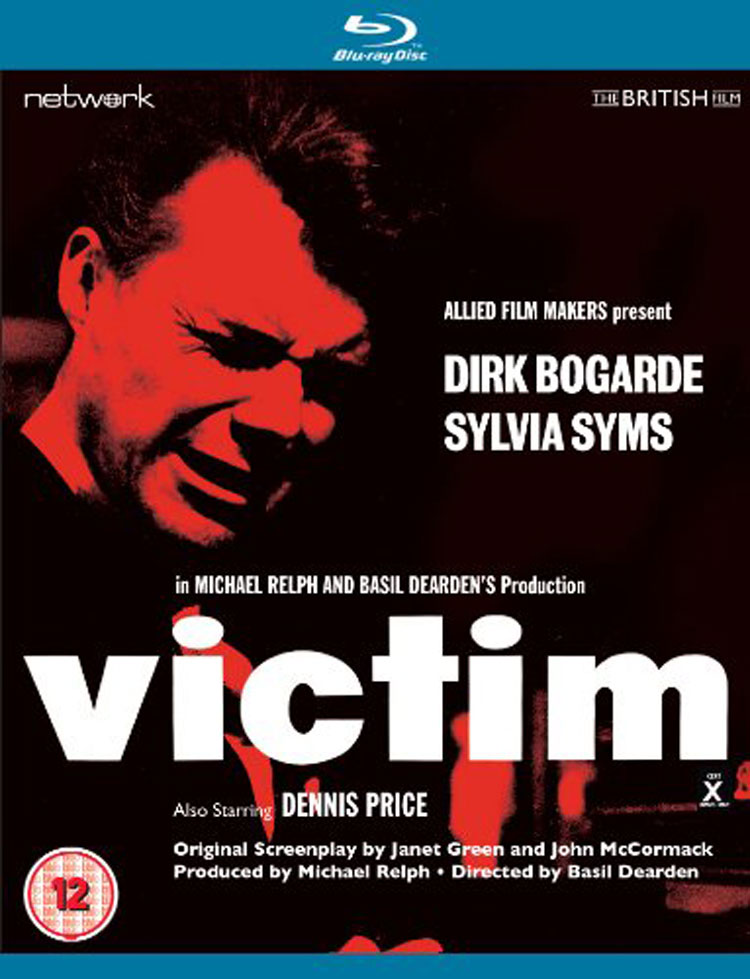

Director: Basil Dearden

Running Time: 100 mins

Certificate: 12

Release Date: Out Now (UK)

Although Victim wasn’t the first LGBT-themed movie ever made (underground efforts and plenty of films that dealt with it through allegory came first) it still holds a special place in the history of gay cinema. For a start it’s believed to be the first mainstream English-language movie to use the word ‘homosexual’, as well as the first to explicitly make gay men (including the main character) its main subject and to show them in a sympathetic light.

It came at a time in Britain when there was a fair amount of debate over homosexuality (or at least more than there’d ever been before). In 1957 the Wolfenden Report – a commission set up to look at the laws surrounding homosexuality in the wake of a series of prosecutions against high-profile people purely for having engaged in gay sex – recommended that “homosexual behaviour between consenting adults in private should no longer be a criminal offence”. This wasn’t just because they thought that prosecuting people for what they do in the privacy of their own homes was pointless, but because there was a large problem with gay people being blackmailed over their sexuality. Some estimates say up to 90% of blackmail cases at the time involved homosexuality in one way or another.

In fact in several countries, including the US and UK, when gay people were flushed out of government and official positions during the Cold War, the problem wasn’t purely that they weren’t straight, but that it was thought they were an unacceptably high blackmail risk.

Despite the Wolfenden Report, foot dragging by the government meant that gay sex in England and Wales wasn’t decriminalised until 1967. Victim is very much a product of its time, coming between these two key moments in the history of gay people in Britain. It’s a pro-gay film which was incredibly progressive for its time, but if it were made today it would be seen as filled with self-loathing, and full of attitudes that many would feel were actively homophobic. It just shows what a difference 53 years can make.

The film’s position is essentially that homosexuals do indeed have an unfortunate affliction – and even the gay people in the movie agree children need to be protected from knowing homosexuality exists. However, just because these people are perverts it doesn’t mean they should be blackmailed and locked up for it, especially as they can’t stop being perverts (that’s as long as they shut up about it and go and be freaks in the corner away from everyone else, of course).

Well, it’s not quite that bad, but that’s the general gist.

While these are very old-fashioned ideas now, it was an incredibly progressive stance for the film to take at the time. The idea of equal rights and general social acceptance for LGBT people wasn’t even a pipe dream in 1961 and would have been seen as ludicrous if espoused in a mainstream movie at that time. Many gay people back then did indeed view their sexuality as an unfortunate affliction. The best they thought they could get was not to be sent to prison for it, with many feeling their sexuality was punishment enough without the law getting involved.

The film follows prominent lawyer Melville Farr (Dirk Bogarde), who’s married to the beautiful Laura (Sylvia Syms). He’s startled when he’s contacted in relation to a young man known as Boy (Peter McEnery). Boy is on the run, although initially we aren’t told precisely why. However it turns out he’s gay and is being blackmailed over it. He’s been embezzling money but can’t come up with all the cash the blackmailers want. Now the police want to take him in, with Boy expecting not just to be prosecuted for the embezzlement, but also for being gay. Rather than allow this to happen, he kills himself.

When Melville discovers what has happened – as well as that it was a relatively innocuous photo of the two of them together that Boy was trying to keep from the police (which while not sexual could have nevertheless caused both of them problems) – he decides he’s got to do something about the blackmailers.

While he insists he’s never acted on his urges, Melville knows that underneath his marriage and respectable career he’s gay – and riddled with guilt about it – and that if he gets too involved in bringing down the blackmailers, he could risk prosecution himself. That’s not to mention that the mere insinuation he was gay could ruin his high-flying legal career. Even many of the other gay men he talks to would prefer him to stop his crusade, as they’re afraid it will result in the blackmailers unleashing evidence that the police could use to put them all in prison.

Victim does a very good job of illuminating what was an intractable situation – as long as gay sex was illegal it made it very difficult for gay people to do anything about being blackmailed, without them risking prison themselves. It wasn’t theoretical either, as there’s a long list of men who sought the police’s help for blackmail and other crimes, but who ended up being prosecuted themselves. For example Alan Turing’s conviction for gross indecency stemmed from the fact he’d been robbed, but when the police found out the culprit was likely to be an associate of his lover (because that’s what the genius told them), they prosecuted Turing while the robber pretty much got away with it.

Victim is a rather melodramatic movie, but it’s a surprisingly effective and entertaining one. The whole thing is initially set up as a mystery, where someone is on the run but we don’t know why. The movie at first makes you think Boy may be a villain, before shifting him to become a very tragic figure. It’s a great way of pulling you in as well as setting up the insecurity and dangers of gay life at the time, even if you’re not initially told it’s gay life it’s dealing with.

From the perspective of the 2010s you can see how the film is trying to carefully negotiate with its audience – introducing its subject slowly and setting up the inherent unfairness of what’s going on – as well as that it’s the blackmailers who are the real criminals here – without saying exactly who it is that it’s being unfair to. It means that when it comes to directly dealing with homosexuality – and more particularly acknowledging the main character is gay himself – the groundwork is already laid to make it seem comparatively sympathetic. The presumption seems to be that in 1961 you needed to show these people as human before you said they were gay, because if you acknowledged they were gay too soon no one would listen to a word they said.

There are times when it feels a little like we’re getting a 1961-style gay rights lecture, but you can understand why they needed to do that at a time when few people knew anything about homosexuals. It also helps us to understand today what it was actually like back then and the viewpoints of the time.

Dirk Bogarde is excellent in the lead role, bringing just the right level of gravitas and pathos to the part. It was a significant departure for the actor, who’d made his name as a British matinee idol. By the late-50s he was the biggest star in Britain and a larger draw for UK audiences than any Hollywood figure. Victim was therefore a big risk, both due to the fact that at the time it could have been career suicide and because Dirk was gay himself.

Or at least it’s presumed he was, as he managed to write several volumes of autobiographies that never mentioned his sexuality and throughout his life he always insisted his exceedingly close male friendships were platonic. However others have come forward to say these men weren’t just his chums, and that Anthony Forwood, with whom Bogarde lived for many years, was indeed his lover.

Generally Bogarde was extremely closed about that side of his life, at least publicly, and you can see from Victim why that might be. There’s an interesting interview on the Blu-ray conducted just before the release of Victim, where Bogarde is more than willing to talk about homosexuality in the context of the movie, but resolutely refuses to discuss anything revolving around his own personal life, despite the fact it takes places in Dirk’s house. It’s also interesting in terms of the interviewer, who noticeably tenses up when the subject gets round to anything gay, as if he can barely believe he’s having a serious conversation about the topic on camera.

Bogarde’s blanket denials about his sexuality became increasingly surprising to many, particularly later in his life, as there was probably no actor of his generation who’d done more to address the topic on screen. Along with Victim there were films such as Death In Venice – which many see as the beginning of modern independent gay cinema – The Servant and to a certain extent Accident. When Dirk said that he wanted his roles to do the talking, he wasn’t joking, but with Victim he made an exceedingly brave choice which has left us with an interesting and entertaining film that is also one of the most important documents on gay life in the UK in the 1950s and early 1960s. And on Blu-ray it looks great, with a lovely crisp black and white transfer that’s a great step up from DVD.

Overall Verdict: Although not a masterpiece, Victim still works well today and if you’re interested in gay history, it’s a movie you have to see. It may sometimes feel like an archaic gay rights lecture, but it’s nevertheless an involving and well-made thriller that brought homosexuality to the filmic mainstream for the first time.

Reviewer: Tim Isaac

Leave a Reply (if comment does not appear immediately, it may have been held for moderation)