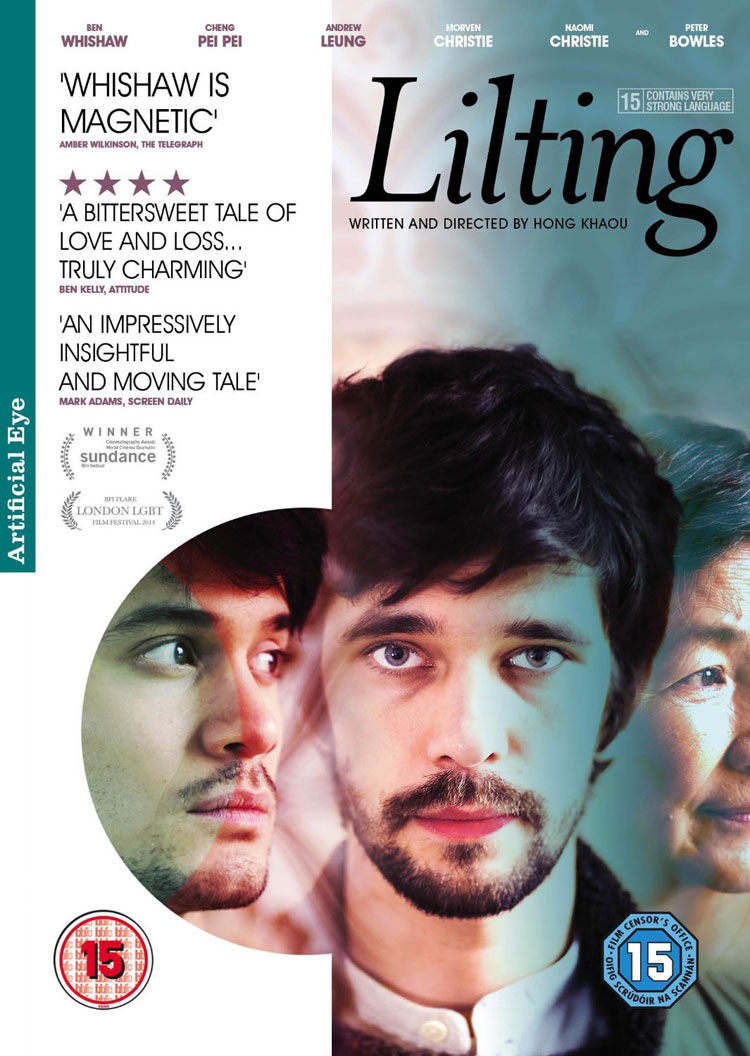

Director: Hong Khaou

Running Time: 91 mins

Certificate: 15

Release Date: September 29th 2014 (UK)

An aging Cambodian-Chinese woman (Cheng Pei Pei) talks to her son, Kai (Andrew Leung) in a nursing home. However he’s not really there. It’s her remembrance of the last time she saw him a few weeks before, the day before he died. Now she is left alone, living in Britain but unable to speak English.

Her son’s partner, Richard (Ben Whishaw), wants to help her, even though he’s going through his own grief, something that’s complicated not just by the language barrier but also because Junn didn’t know her child was gay (or perhaps she did know but was in denial). Richard’s remembrance of his lover revolves around his gentle coaxing of him to come out, so that perhaps Junn can come and live with them, something he hopes will assuage the guilt he knows Kai feels. Now he still wants to help Junn, but she’s not sure she wants his help, partly because she always disliked him and doesn’t trust him.

Lilting is a quiet, deliberately measured film that avoids treating grief with the histrionics that many movies use, instead looking at people trying to find a way through and to do the right thing. Brought into that are all sorts of interesting ideas, from the difficulties faced by second generation immigrants and romance when there’s no shared language, to the problems for gay people if their partner dies before they’ve come out.

While Richard could easily have come across as a bit of a plaster saint, Ben Whishaw brings the openness he’s so good at, where his character’s complex emotions are only a hair’s breadth under the skin. His relationship with Kai is sweet and rather sexy, and while initially it seems curious that the only thing they ever talk about is him coming out, as the film goes on it becomes clear why this is what we’re seeing.

Cheng Pei Pei has in many ways the most difficult job, playing a woman who seems needy and somewhat selfish, whose moody demands on her son appear unreasonable, and who dislikes Richard not because she thinks he’s gay, but because she’s jealous of her son’s ‘friendship’ with him. However she manages to bring great warmth to the role, ensuring you realise that her clinging is a confluence of the fact her son is the only person she has left both in her family and her language, and also that she is in declining mental health and scared for her future.

In the script you can feel writer/director Hong Khaou’s empathy and frustration. This is an intensely personal story for him and that’s what really drives the movie. He brings a sense of melancholy and yet hope, which is extremely moving at times, with the grief writ large even if the characters aren’t hollering, screaming and crying all over the place. Khaou also handles the character’s sexuality well, ensuring Richard and Kai feel like a real gay couple and that the issue of coming out is again dealt with in a realistic yet quiet way.

The movie does have a tendency in the middle to slow down almost to a state of torpor and there are a few artistic filmmaking contrivances that feel unnecessary, but largely it’s a great watch.

Overall Verdict: A quiet, contemplative and moving film, with good performances and an interesting take on living as an immigrant and coming out.

Reviewer: Tim Isaac

Leave a Reply (if comment does not appear immediately, it may have been held for moderation)