Director: Jack Gold

Running Time: 77 mins

Certificate: 12

Release Date: June 5th 2017 (UK)

It’s difficult to imagine nowadays what audiences would have made of The Naked Civil Servant in 1975. Gay sex had only been (partially) decriminalised in England and Wales eight years before, and homosexuality certainly wasn’t seen on screen much. Then suddenly there was a primetime TV movie in the UK, about someone who didn’t even have the common decency to hide in the shadows and pretend being gay was the most shameful thing in the universe!

The film charts the life of Quentin Crisp (John Hurt) from his youth through to his 60s. As a young man, his parents don’t know quite what to make of their fey son, who doesn’t seem to like girls or be able to fit himself into ‘normal’ society. After meeting a bunch of ‘effeminate homosexuals’ in London, Quentin starts wearing makeup and becoming increasingly ‘noticeably gay’ at a time when homosexuality was one of society’s most detested things.

At first he makes money as a rent boy, before getting work as a commercial artist and a life model. With his conflicted feelings about love – and whether love is even real – he decides that rather than looking for the ‘great dark stranger’ who will capture his heart, he will dedicate himself to being so out that everyone will know what and who he is, showing them that gays people are just people. However, with his feminine look, not everyone is willing to accept him. This leads to beatings, being barred from military service during the war, and the police unjustly arresting him for soliciting sex.

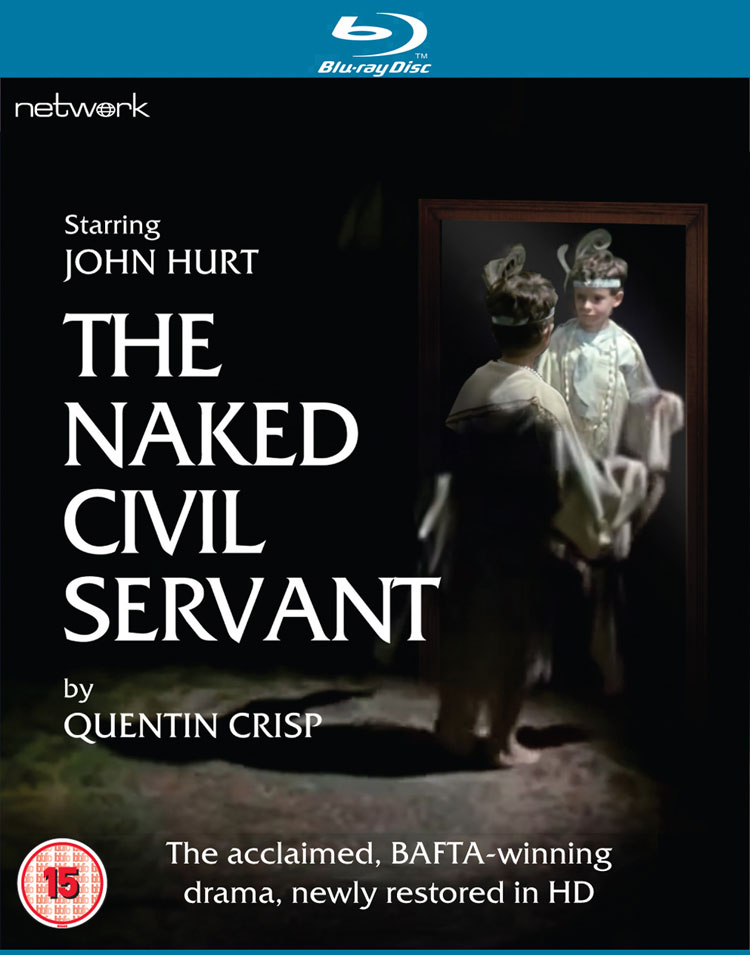

John Hurt won a BAFTA for his role as Crisp. It’s a tour-de-force and an impressive impersonation – so much so that in the popular imagination it’s become difficult to know where Hurt ends and the real Crisp starts. The Naked Civil Servant opens with the genuine Quentin talking to the camera, which at the time was presumably to help show audiences not used to this sort of thing that this over the top eccentric was a real person.

Nowadays the movie is as much a historical document as it is an entertaining film. Made so close to the events, it’s a privileged look at being gay in England at a time when documenting the lives of LGBT people was incredibly rare. That said, at any time in history Crisp would have been a singular person.

Nowadays his ideas and attitudes would be seen as more than a little problematic, and the film does show how he was a mass of contradiction. Crisp had a tendency to talk as if he speaking an endless stream of great aphorisms, and as if he was the official spokesman for all that was gay. However, growing up with no frame of reference and at a time when he’d have been told being gay was wrong almost since birth, his ideas were inevitably based around himself and how he viewed life, resulting in a very particular, unusual, and rather misanthropic/homophobic worldview. Then, when he’d transferred that rather blinkered perspective into a pithy observation, he’d treat it as being true for all gay people and for the world in general, and make sure as many people knew about it as possible.

In The Naked Civil Servant, he is determined to be out and proud, but riddled with shame over his ‘condition’. He’s an atheist in fear of God. He’s proud of his status as an effeminate homosexual, but utterly ambivalent about actually being with a man – indeed he seems to treat the actual business of being gay as a bit of an annoying chore. He is adamant he will be himself no matter what society says, but even he realises he’s doing a performance of being himself and really he’s someone else.

There are moments in The Naked Civil Servant where you wonder if in the modern day he would identify as genderqueer or trans (Crisp always insisted he was a man, but that it would have been easier if he was a woman), or whether he would have seen himself as aromantic or asexual. Undoubtedly though, despite his mission to live in a way where others would know he was gay, the film shows that he is absolutely riddled with internalised homophobia (even if that term didn’t exist at the time), and constantly wanting to forgive society for its hatred towards him rather than actively rail against it. And that’s largely because no matter what he says, society’s attitudes are still ingrained within him.

It would have been easy for the film to come across as confirming the prejudices of the time – that gay people were ‘weirdoes’, incapable of real love or lasting relationships (something Crisp actually believed) – but through the astute screenplay and Hurt’s brilliant performance, it instead brings out the basic humanity of Quentin. He is a unique person in a unique time, whose unfortunate lot in life wasn’t to be born gay (although Crisp himself often suggested it was) but to be born into a society with so little understanding and compassion. It also suggests a sense of naiveté in Quentin, both about himself and the world, so that despite his tendency to talk like he’s speaking the truths of the universe, the viewer is aware that he may just be a constituency of one.

It is a fascinating film, and while it’s difficult to tell how truthful it is to the gay experience between the 1930s and 1970s, it undoubtedly gives an interesting insight into a hidden world, and one of its more singular members. The Blu-ray offers a fairly crisp picture, and the option of watching The Naked Civil Servant in either its original TV 4:3 aspect ratio, or a widescreen 16:9 version.

There are also a couple of good historical offerings in the special features for those interested in more about the real Quentin Crisp. Included on the disc is an episode of the documentary series ‘World In Action’, made around the time The Naked Civil Servant aired, which takes cameras into Crisp’s tiny London apartment (which he literally never cleaned) and talks to him about his life and ideas. It’s a good display of both how accurate Hurt’s portrayal is, as well as Quentin’s aphoristic way of talking (indeed, he repeats several of his pithy lines that made it into the film, word-for-word). Again it underlines his singularity, such as how he pontificates about the impossibility of being happy in ways where he seems to think he’s talking universal truth, but anyone watching will just wonder how he doesn’t realise he’s the only one who feels that way. As in the film, it shows how he turned rationalisation, transference and internalised homophobia into an artform.

There’s also an episode ‘Mavis Catches Up With…’ from 1989, where Mavis Nicholson talks to Crisp, comparing an interview she did with him in the 1970s with how he is in the late 1980s when he’s living in New York (John Hurt also captured that time in Crisp’s life in 2009’s An Englishman In New York). It displays a man who was still uniquely himself, but who perhaps as he reached 80 years old and was living in a world where gay people weren’t hiding as much anymore, had realised he didn’t really speak for anyone but himself. He is still outspoken, but there’s undoubtedly an edge of self-awareness that previously seemed lacking.

Through most of his life he’d been a lone voice, and without any backup or frame of reference for being out and proud, he’d assumed his experience was more universal than perhaps it was. This resulted in him espousing plenty of ideas that would be seen as unpleasantly homophobic these days. Indeed, by the 1980s, there were already plenty who were ready to take him to task for things such as saying that AIDS was a fad, that the world would be better without homosexuals and for his dismissiveness of the gay liberation movement (which some felt was a subconscious anger on Crisp’s part that he wasn’t unique anymore).

In The Naked Civil Servant, Crisp famously describes himself as one of the ‘stately homos of England’, but by the 1980s quite a few people were prepared to say that while that homo was important for its time, now it was dilapidated and needed to be left behind. The episode of ‘Mavis Catches Up With…’ suggests that perhaps in his old age, he was starting to realise that the world had moved him by and he was a lone voice from a different world. That said, up until his death in 1999, he still had a tendency to say things that now would be considered horrific (not least that if you could tell if a baby was gay in the womb, it would be better to abort it).

Crisp is treated by many as a trailblazer, but even in The Naked Civil Servant he isn’t really that. He is a singular creation of his own, and while determined that everyone should see he’s gay, he is more an observer than someone who was changing hearts and minds (indeed, it’s another contradiction in Crisp, that he seemed so bothered by what society thought and how they treated people like him, while never really wanting lasting connection to other human beings). Nevertheless, it’s still a fascinating film about an intriguing if problematic person, who never quite got over or realised how much self-hatred had been instilled in him from birth.

Overall Verdict: Hurt’s performance still shines through in an entertaining film about a true eccentric. Crisp may have been contradictory and problematic, but he undoubtedly led a singular life that’s given us this unusual insight into gay life in England in the mid-20th Century.

Reviewer: Tim Isaac

Leave a Reply (if comment does not appear immediately, it may have been held for moderation)