Director: Bavo Defurne

Running Time: 56 mins

Certificate: 12

Release Date: February 6th 2017 (UK)

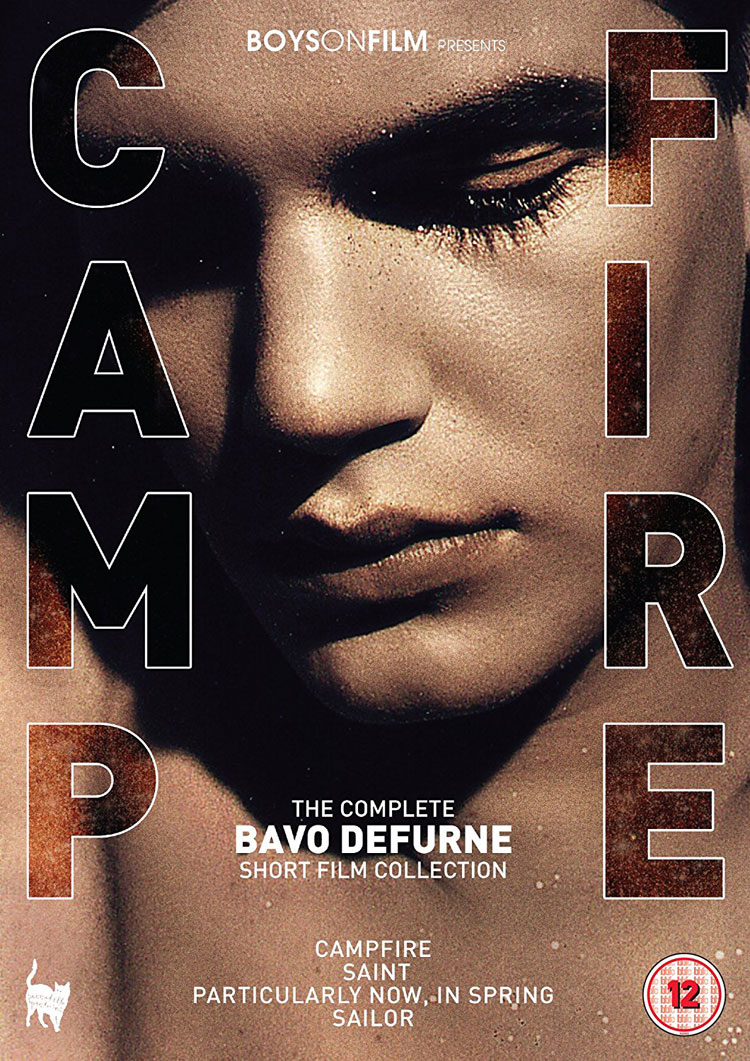

Over the last few years Peccadillo Pictures has done a great job promoting gay short films with its Boys On Film DVD collection. Now though we’ve got something slightly different, a ‘Boys On Film Presents’ release, which rather than bringing together the works of multiple different directors, focuses on the work of one filmmaker, Belgium’s Bavo Defurne.

Defurne got lots of praise for his 2011 movie, North Sea Texas, a coming of age tale about a young gay man. However, before he made his feature debut with that movie, he’d gained an impressive reputation with his short films, which were lauded at film festivals and championed by the likes of the BFI. That is perhaps because of the way he manages to link the past of gay cinema with the present, such as the short Sailor (aka Matroos) being reminiscent of Fassbinder’s Querelle or the way Particularly Now, In Spring and Saint evoke the look and feel of Un Chant d’Amour (both of which are not coincidentally linked to Jean Genet).

This release brings together all four of Defurne’s most acclaimed short films, which some will find fascinating, ethereal and challenging, while other while find them a little too idiosyncratic and experimental for their tastes.

Particularly Now, in Spring is the earliest of the four Defurne shorts included. It’s a very low-budget black and white film, which consists of footage on young men in and around a swimming pool and locker room, while one of the men muses on his thoughts and feelings in voiceover. It’s an odd film, as on the surface it seems oddly pointless – footage of young men in swimming trunks and the somewhat juvenile ramblings of a youth. However, that is essentially the point. The film is an attempt to capture youth and the promise of what young people can become.

The ‘ramblings’ are really about the moment when a teen’s mind is still both childish and becoming an adult, when it’s realising what the bonds between boys may mean, and that they are not solely an extension of their parents. Yet, there’s still a naiveté to what the boy says, where the world is yet to trample of even the unlikeliest of dreams. The young man is waiting for a French man who might make him a star, and in a rather Godot fashion, accepts he way be in for a long wait.

Both Particularly Now, in Spring and the next film, Saint, were made in the mid-to-late 1990s, but use black and white film stock that gives them the look and feel of something much earlier. If you didn’t know anything about them, you could easily believe these were films from the 40s or 50s, which adds to their intrigue.

Saint is a stylised take on the martyrdom of Saint Sebastian, a gorgeous young Roman man who is taken to the woods and shot and killed with bows and arrows. There’s little context to tell us why he’s being killed, but a young boy blows a horn which calls others to witness this event, while the executioners seems to have second thoughts about killing him.

Saint Sebastian is an odd figure, who thanks to the world of art since the 14th Century he has become the ultimate icon of twink murder, with endless images of a beautiful young man wearing nothing but a loincloth, shot with arrows yet looking serene as if pain cannot touch him (ignoring the fact that in real-life he was 40-something and stoned to death, not shot with arrows). The likes of Oscar Wilde and Tennessee Williams have since turned him into the virtual patron saint of homosexuality. No one is entirely sure why, as the story of Sebastian has little to do with gay-ness – it’s to do with how he’s been depicted in art. it’s not just the fact Sebastian was martyred and is always shown as beautiful and serenely accepting his persecution, but also perhaps because of ideas about pain being pleasure and the destruction of beauty.

Some of these things are hinted at in Defurne’s take on the tale, contrasting the violence of the close-up wounds with the beauty of the scene at a distance. Largely though it seems to be about building intrigue and trying to get the audience to consider what they’re watching, such as the contradictions of eroticising death, and the issues of voyeurism. It’s a strange, ethereal short, but it’s oddly intriguing.

Next up is Sailor, where a young man in a bath dreams about his sailor friend. His fantasies take him to exotic lands, shown to us in hyper-coloured, stylised visions. However, his fantasies begin to be touched by worries about what’s really happening and how he fits into it. It’s an odd little film, but it’s easy to fall into its dream-like spell, even if initially it’s difficult to understand what you’re seeing – what’s fantasy and what’s real, what small moments mean and what exactly the relationship between the men is?

Sailor is often real yet obviously false, beautiful and yet strangely kitsch, evocative of the past yet with modern sensibilities. It also does a good job of evoking the fantasies and fears of young love – that in your head there seem to be endless possibilities, and yet that same head can create anxiety and trepidation that may or may not be real.

The final film is Campfire, which is by far the most accessible and easy to digest of the movies. As with the other shorts, there’s a fascination with youth and the moments of gay awakening and desire. In the film, a group of young people are camping during the summer. One of the boys tells his girlfriend they should separate, and that evening he ends up sleeping with his male friend. However, the next morning the friend is freaked out about what’s happened and shuns the boy. Eventually it leads to what may be reconciliation or possibly violence.

Campfire tells a story that many will recognise, showing a fascination for the fears and hope of first expressing your sexuality, and perhaps most pertinently empathising with the pain that can come from realising others may not feel the same way you do. There’s also a good feel for the vagaries of youth, harking back to Particularly Now In Spring’s sense of how in the moment things may feel dramatic and permanent, but in the world of youth are over in a second.

Overall Verdict: These four Bavo Defurne shorts aren’t a collection for everyone, but if you’re interested in something a bit challenging and which cannot help itself but train its camera lens on the beauty of youth, you should find plenty to appreciate.

Reviewer: Tim Isaac

Leave a Reply (if comment does not appear immediately, it may have been held for moderation)