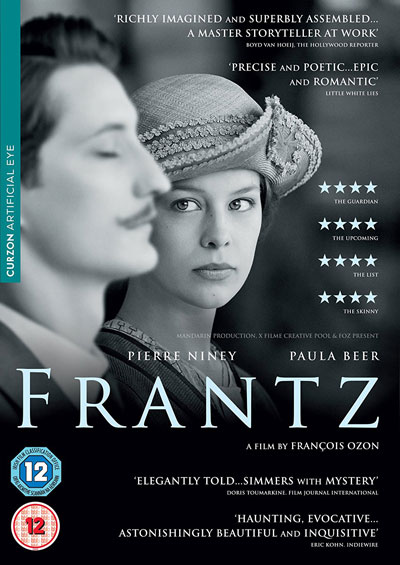

Director: Francois Ozon

Running Time: 113 mins

Certificate: 12

Release Date: July 10th 2017

I’ve generally shied away from covering movies on BGPS where the gay content is all down to interpretation, but it’s well worth reviewing Frantz here – a film that could either be very gay or barely at all depending on how you look at it. Just from reading the synopsis I suspected that it might be a film like that, due to the presence of director Francois Ozon (Swimming Pool, 8 Women), a filmmaker whose career has been marked by a strong interest in female characters, gay desire, and how different people interpret the same things.

It’s just after World War I, and in a small German town a young woman called Anna (Paula Beer) is still in mourning for her fiancé – Frantz – who she lost in the trenches of France. She lives with her fallen boyfriend’s parents – Hans (Ernst Stötzner) and Magda (Marie Gruber) – who are also still reeling from the loss.

When she visits Frantz’s (empty) grave, she is surprised to find fresh flowers there that neither she nor Frantz’s parents left. She is told they were put there by a mysterious Frenchman who has arrived in town. The visitor is Adrien (Pierre Niney), who has travelled to Germany in memory of Frantz. He tells Anna, Hans and Magda about how he and Frantz were friends in Paris before the war, but that world events caused them to end up as soldiers on different sides of an almighty conflict – one of them surviving while the other didn’t.

However, there is far more to this tale than Adrien first reveals, which eventually leads Anna to Paris, revisiting the place Frantz would have known as a student, as she attempts to track Adrien down.

Inspired by Ernst Lubitsch’s 1932 movie, Broken Lullaby, which in turn was based on a play by Maurice Rostand, Frantz is a rather fascinating movie, playing with time, memory, forgiveness, romance, the traumas of war and the possibility for redemption, many of which are deliberately shown in ways that make them as relevant today as they were back in 1919. However, it doesn’t do it in a straightforward way, instead laying out a series of possibilities for the viewer to look at and decide what they mean, what is true and how that changes what is important to the story.

For example, you have characters finding strength and solace from reliving events that may never have happened. It plays with the idea that sometimes there is a better ‘truth’ than what actually occurred, especially if that factual truth is slowly destroying people, while a fictionalised reinterpretation may help them. Indeed, there’s a suggestion that the truth of what something represents is more important than the objective reality.

It’s a theme that runs right through the movie, such as how both the Germans and the French prefer to hate and blame each other for the war and for killing each other’s young men, so they don’t have to consider their own culpability (especially that it was the parents who encouraged their children to go off to war).

All the way through, what characters know and believe alters, often due to lack of information, but other times due to a wilful decision to either lie or to find solace in what they know isn’t strictly true. It allows it to be a powerful look at both war and people picking up the pieces afterwards, while also speaking to how we all live our lives – ignoring truths that don’t fit with what we’d like to believe, and turning things into narratives that are far less messy, complex and morally grubby than reality. It’s not just the characters either, as the viewer is also asked to question what they believe and what is true in the movie, and how the dissonance between the possibilities changes what they’re viewing.

That brings us to Adrien. It’s slightly difficult to talk about him without it being too much of a spoiler. However, right the way through the movie it’s possible to see him as a gay man or as a straight one. Normally that would be annoying – either a film unwilling to tell the truth or a too-pleased-with-itself filmmakers’ affectation. Here though it fits perfectly with a film where people are creating realities for both themselves and for the sake of others.

Adrien’s remembrances of Frantz are undoubtedly given a homoerotic edge and intimacy that he lacks in his other interactions – to the point that the flashbacks are so vibrant and intense that they’re one of the few colour sequences in an otherwise black and white movie. There is also a lover’s embrace between two men in a trench, but one where the embrace is forced rather than optional.

However, as we learn more, all this is brought into question – both in terms of the actual truth and what a remembrance of intimacy might actually mean. At no point is Adrien’s sexuality directly addressed, resulting in a scene towards the end that could be about a gay man and a straight woman, or two straight people in an impossible situation. What they could be getting from that moment may be completely different depending on how both the viewer and the characters interpret it, and it may be that in reality they are both the surrogate for the same person who isn’t there. It presents something where there are possible layers of truth, the least important of which is the objective reality.

Is he gay? Is he straight? And if he is gay, what does that mean about the ending, comparing what Anna believes has just happened with what may be going on in Adrien’s head? It’s certainly not a coincidence that Ozon is gay, and the original playwright, Maurice Rostand, was a closeted man too – so the movie is undoubtedly iffused with a gay sensibility, but the ‘truth’ about Adrien is left up to the viewer.

In most films, the objective truth is held up as the ultimate prize irrespective of the pain it may cause – but Frantz shows the world is more complex than that, and that even those who may say they only want truth, might really want something a little more comforting.

Overall Verdict: A gay-themed film, or not, depending on how both you and the characters want to interpret things. This exploration of the aftermath of war becomes a fascinating look at the nature of truth, how malleable it can become, and that we all create our own reality depending on what we think will help the most. Sometimes it may help, and other times it just helps us hide.

Reviewer: Tim Isaac

Leave a Reply (if comment does not appear immediately, it may have been held for moderation)